Kien, the most delayed video game in history, released after 22 years | Games

TheIn 2002, a group of five Italians made local news: they would be the first company in the country to develop a game for Nintendo’s popular mobile phone, the Game Boy Advance. The team raised several hundred euros and several computers to prepare for the project. They had no experience making games. They didn’t even have programmers. All they had was a love of video games, a shared hatred of working for bosses, and an endless optimism.

For the next two years, the group worked away. Late nights were common and the team barely got any rest. It was a grueling time, but they were determined to make an ambitious game with complex features. Her name was Kien. If you haven’t heard of it, it’s because it never came out – until now. The platformer action didn’t see the light of day until this year, by which time most of the original team had long since moved on. Only one member of the group of five remained: game designer Fabio Belsanti, who never lost faith in the project.

Kien currently holds the record for the longest delayed video game in history – 22 years eclipsing the 15-year journey of the infamous Duke Nukem Forever, a shooter that was so delayed it became a meme. After all this time, people can now buy Kien, on a Game Boy Advance cartridge.

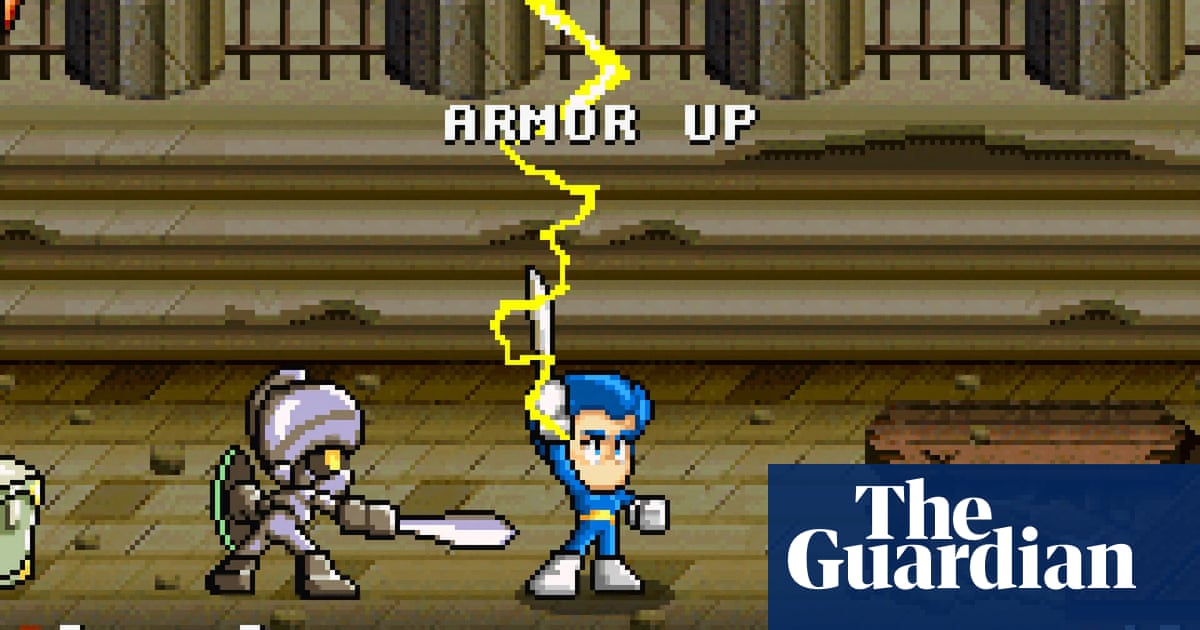

The game begins by asking the player to choose between its two protagonists – a warrior and a priestess. The warrior can use a sword to kill his enemies, and there are many of them. I died repeatedly in that first level. Armored skulls are plentiful and they respawn after a short time. You can’t let your guard down in Kien, which may be why Belsanti compares it to a Dark Souls primordial. It reminds you of that weird game you took a chance on when you were a kid, maybe because the artwork looked weird, or maybe it was the only thing left on the shelves of your local movie rental place.

Of course, the plan was never a release plan for many decades. The game was finished years ago and many publishers expressed interest in it. After choosing one, the winds shifted for Belsanti as Kien’s publisher of choice conducted some market analysis that determined his game was too risky to support. At the time, each Game Boy cartridge cost $15 to produce.

“The amount of capital required just to print the initial copies was daunting, especially since the chances of commercial success were low, based on industry trends at the time,” says Belsanti.

But despite this obstacle, Belsanti continued to hope. He had attended university in Tuscany, where he spent a year immersing himself in the archives of unpublished 15th-century books. These were chilling tales of a mercenary company in the early Italian Renaissance, comprising knights, soldiers, and soldiers—but because of their age, these stories essentially lost time. Kien is inspired by these tales, the unusual graphic style of early Japanese games, and action games like Turrican. Despite its age, Belsanti considers Kien to be a pioneer of its kind, similar to games like Dark Souls. The non-linear fantasy gameplay is unforgiving, but players are rewarded with a compelling story about a lost civilization.

As Kien languished in development limbo, the company Belsanti founded, AgeOfGames, had to find a way to survive. “The capitalist system is a merciless meat grinder,” he says, “to which I have adapted out of necessity, but I don’t like it.” The company found a niche in educational games. One of their biggest successes so far has been ScacciaRischi, a platform game developed for Italy’s INAIL, a non-profit group dedicated to helping people prevent injuries and illnesses at work. It has been played by tens of thousands of students and has addressed topics such as the Covid-19 pandemic.

AgeOfGames may have continued this way forever, but a change in the gaming industry suddenly made Kien an opportunity again. Within the past five years, a boom in the retro gaming scene has revived interest in outdated hardware and rare games, which can fetch thousands on the resale market. Not only have the manufacturing costs of GBA cartridges come down, but companies have also grown to meet this demand.

“I believe we are at a similar stage [the revival of] vinyl or cassettes for music, Belsanti thinks, “a return to earlier, more primitive forms of the medium driven by the nostalgia of the generations who lived through those eras and the curiosity of those who came after such technology”.

after promoting the newsletter

Kien’s new publisher, Incube8, specializes in making games for classic consoles – and is supporting Kien. The game is now being sold in an eye-catching transparent gray cartridge. The game box also comes with a multi-page manual, a package that has practically disappeared from modern games.

“On a romantic level, the thought of releasing the game on its original console is just magical,” says Belsanti. “Seeing Kien come to life on the platform it was designed for is a dream come true.”

Now, AgeOfGames is working on a spiritual successor. As he did more than 20 years ago, Belsanti is hopeful that the public will see the value in a game like Kien, even if it doesn’t have advanced graphics or fancy bells and whistles.

“The power of the video game experience, not always, but in some cases, can be much more intense and powerful in older video games made with limited graphical and technical resources,” says Belsanti. “I’ll never forget the thrill I felt seeing the cover art of my Philips Videopac or Spectrum ZX or Commodore 64 video games, which had nothing to do with the pixels displayed on the screen. My imagination created a bridge between the artwork and the pixels and filled every boundary and void with fantastic stories.”

Post Comment